ART NOUVEAU

late 1800s–1910

ART NOUVEAU LATE 1800s – 1910

Every prevailing aesthetic has a counter-movement, and so it was with Art Nouveau, a revolt against the industrial age and its classical, formulaic designs. The movement took hold in Paris, with sensuous, organic forms shaping decorative arts and architecture—most famously, the Paris Metro entrances.

In Art Nouveau jewelry, the female form was a recurring theme and beautiful women were often depicted as enchanted nymphs, fairies or mermaids—an outright scandal to the prevailing Victorian and Edwardian sensibilities. Natural themes were also important: butterflies, dragonflies and beetles flitted about pendants and earrings, while peacock feathers, orchids, water lilies and ferns wound their way around bracelets and rings.

Art Nouveau championed hand craftsmanship and naturalism over precious materials and overt displays of wealth. Less expensive materials, such as silver, moonstone, horn and other natural elements were widely used. Colorful enameling techniques, such as plique-a-jour and cloisonné, reflected the artisan’s skill. In fact, this was the beginning of the jewelry designer as named artist. The great makers of the period, including Rene Lalique, Louis Comfort Tiffany and Karl Faberge, are renowned for advancing the new style, and their work is highly collectible today. In the mid-1960s, Art Nouveau jewelry found the ideal moment for revival when the era’s dreamy, psychedelic motifs swirled across posters for rock music festivals.

EDWARDIAN

1901–1910

EDWARDIAN 1901 – 1910

Although the Edwardian period officially began in Great Britain in 1901 when Edward, son of Victoria, ascended to the British throne, stylistic elements of the era (known as La Belle Epoque in France) began while his mother was still alive, and continued for a few years after his death. King Edward reveled in luxury, and his rich countrymen followed his lead. Elegance and fashion were the rule, with jewelry glittering brightly at galas in London townhouses and Parisian hôtels particuliers.

metalworking—specifically the invention of the oxyacetylene torch, which could reach very high temperatures—allowed jewelers to forge airy, lightweight designs from platinum, which till then had been too challenging to work with. This gave way to the delicate platinum bows, ribbons and tassels of the garland style. Jewelry was often edged with delicate platinum millgraining—another technique made possible by new technology. Necklaces veered in length from the choker to the sautoir—a very long chain or beaded necklace, often terminating in tassels. But in fact, these “new” styles weren’t exactly new; they were inspired by the Court of Versailles of the late 1700s—another era of over-the-top luxury.

RETRO

1935–1950

RETRO 1935 – 1950

The term “retro” gets bandied about to describe all sorts of vintage fashion. But in the context of jewelry, Retro refers to the period of early Modernism that began in 1935, spanned World War II, and lasted through the mid-1950s. During the war and the Great Depression, as women began entering the workforce, clothing became simpler. In contrast to apparel’s thrift and severity, jewelry became bigger and brighter than it had been in decades, taking cues from Hollywood stars like Lana Turner, Joan Crawford and Lauren Bacall.

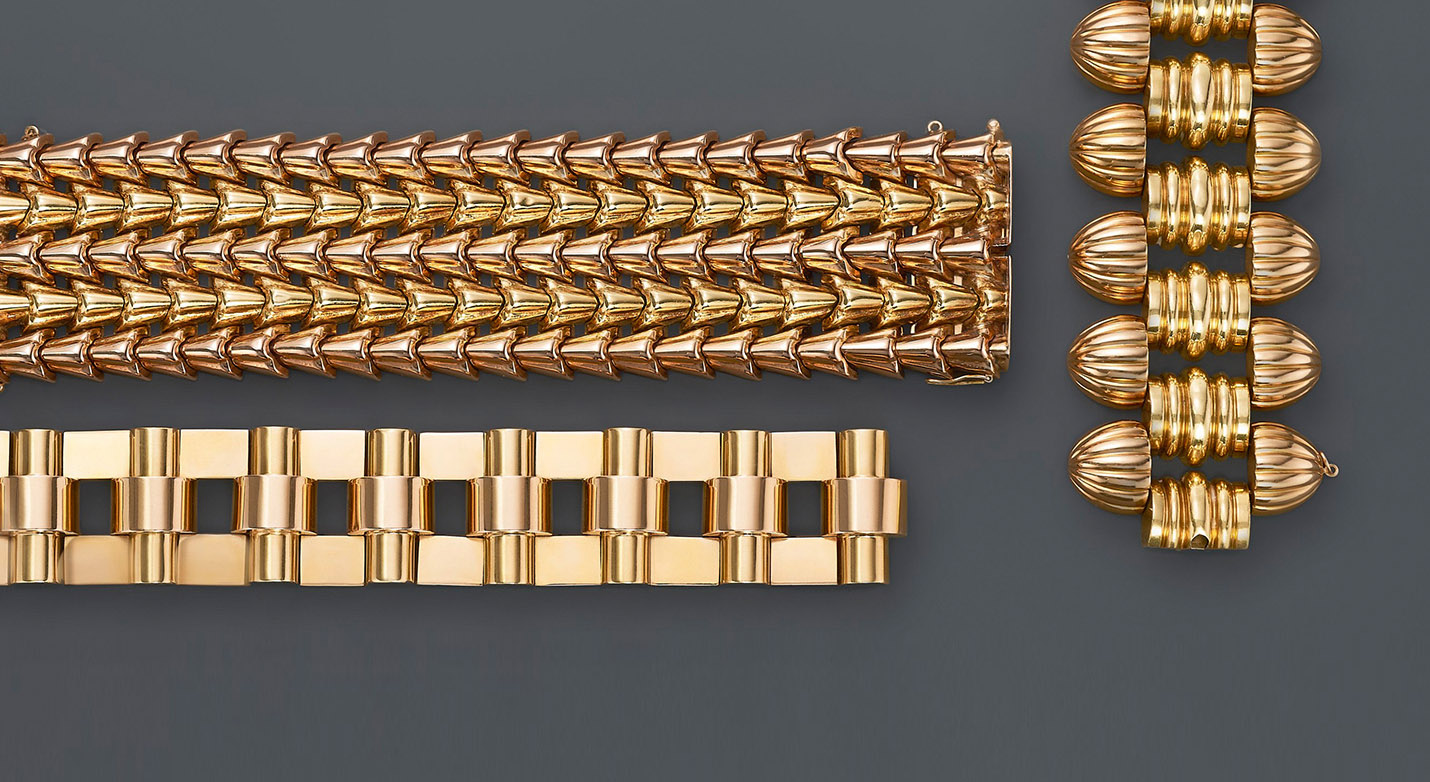

Styles ranged from feminine and romantic, with motifs like birds, flowers and seashells, to geometric and industrial (a sub-category known as Art Moderne), with patriotic and industrial expressions inspired by factory production lines and tank treads. Although the themes differed greatly, the unifying characteristic of Retro designs is that they are highly dimensional, rather than flat like their Art Deco predecessors. Platinum was reserved for the war effort, so gold—not only yellow, but rose and green, too—resurged in popularity. Amethysts, citrines and aquamarines took center stage in bold cocktail rings, and bracelets were especially important: oversize gold links exuded power, while charm bracelets were whimsical and romantic. Clip-on earrings were patented in 1934, which ignited a trend for earrings worn close to the ear.

MID 20th CENTURY

1950s, '60s and '70s

MID-20TH CENTURY 1950s, ’60s AND ’70s

The 1950s were a decade of prosperity and with that came a return to femininity and glamour in fashion. Jewelry designs remained oversize, but were more open and textural than the chunkier styles that preceded them. Diamonds set in platinum were back en vogue. In fact, one of the era’s most indelible images is Marilyn Monroe, sheathed in fuchsia and dripping in jewelry, singing “Diamonds Are a Girl’s Best Friend” in 1953’s Gentlemen Prefer Blondes.

The dynamism of the 1960s was reflected in the bold, bright jewelry of the era. Picture the wide variety of styles depicted on Mad Men: colorful brooches, gemstone bib necklaces, pop art earrings. Opaque materials in vivid colors, such as coral and turquoise, mirrored the hues of the fashion world. Designers looked to Asia, India and Africa for inspiration; the result was a resurgence of gold as well as exotic, global themes. The important makers of the era include Van Cleef and Arpels, Bulgari, Cartier, David Webb, Jean Schlumberger for Tiffany, Harry Winston, Sterlé and Kutchinsky.

Bohemian style continued into the 1970s. Gold still ruled, and the favored gemstones were darker and more natural in color—shades of burgundy, deep blue and purple. By the end of the decade, punk style started to influence jewelers, and spikes and studs—think Cartier’s Juste un Clou—hit the scene.